Railway suicide in Canada

Incidence of railway suicides and extent of the problem in Canada

Over 10 years of records, we can estimate that there is an average of 43 railway suicides per year, with an increase in the last 3 years of records (2005 to 2007).

In Canada, between 2000 and 2009, the most common methods of suicide were hanging (44%), poisoning (25%), and firearms (16%) with important variations by gender and age. By comparison, between 2005 and 2007, rail suicides accounted for a mean of 1.55% of all suicides in Canada.

Summary

- There are 43 completed suicides on average annually commited on railway rights of way

- There appears to be an increase in the number of suicide over the last 3 years of record, this tendency will have to be validated as data is obtained in the coming years.

- The proportion of railway fatalities which are suicides has been increasing: suicides accounted for 30% of railway fatalities in 1999 and 53% in 2007

- For each suicide, at least 6 individuals are confronted with potentially traumatic situations (2 engineers / conductors, at least one police officer from the railway or the community, at least one first respondent, a local manager and replacement crew)

When and where do suicides occur?

Who commits suicide by train?

The suicidal person's behaviour before impact

Behaviour within 24 hours

In order to better plan prevention strategies, it may be useful to know what people did in the hours before they died. The following table summarises information available in the coroners’ files about the whereabouts and behaviours of the suicidal people prior to their death.

| Behaviour during the 24 hours prior to death | N | % |

| Substance use | 116 | 45.8% |

| Contact with own social network | 31 | 12.3% |

| Came with belongings or left belongings near the tracks | 28 | 11.1% |

| Dispute with family or significant other | 23 | 9.1% |

| Sudden emotional changes | 22 | 8.7% |

| Stopped taking their medication | 11 | 4.3% |

| Put their affairs in order, gave things away, left letters | 10 | 4.0% |

| Problem with police or unlawful behaviour | 7 | 2.8% |

| Fight or dispute | 5 | 2.0% |

| Played chicken | 1 | 0.4% |

| Had not slept | 1 | 0.4% |

Vehicle

Suicide victims are mainly pedestrians (94.4%) but this proportion varies by province, with the highest proportion of suicides involving a car in New Brunswick and Québec.

Behaviour on tracks

This information comes from descriptions by railway crew members when this information was included in the coroners’ reports. Since most suicides occur in places where there are no other direct witnesses, there is little information on this aspect of the incidents. However, reports indicate that suicide victims tend to run in front of the train, stand or sit on the tracks, lie down across or between the tracks, face the train and look at the driver or turn their back to the train. Some put their head on the track or put their arms out in a cross position. Some were observed walking along the tracks before stepping in front of the train. Activating the whistle does not entice them to move away. The following table gives some indication of the occurrence of the varied observed behaviour.

Suicide Prevention Strategies

Initiatives in various countries to reduce the number of suicides on railway rights of ways can be considered to follow these steps:

- Analysis of the incidence and characteristics of railway suicides in the targeted areas.

- Analysis of the psychosocial, medical ,and environmental characteristics of railway suicides.

- Analysis of the geographical and spcyo-social context (population, track and traffic density, local suicide rates, presence of mental health institutions, etc.).

- Identification of promising activities to help reduce the incidence of railway suicides.

- Involvment of local stakeholders.

- Implementing activities.

- Evaluating the implementation and effects of each individual activity as well as their overall impact.

Here are a few examples of such initiatives developed in different contexts around the world:

|

Country |

Source |

Project carrier |

stakeholders |

Characteristics of railway suicide targeted by strategy |

Suicide prevention activities |

|

Belgium |

Andriessen, Krysinska (2011) |

Infrabel |

Suicide prevention organisations

Research teams Flemish Suicide Prevention Action Plan |

Hotspots |

Analysis of hotspots and interventions: e.g. Fencing Destroying old platforms Improving drivers’ visibility Emergency call system on platforms Raising community awareness of mental health facilities Improving surveillance and lighting Training staff to identify at risk persons Responsible media reporting |

|

Australia |

Lifeline Foundation. (2012) |

Track safe foundation |

Mental health services Police Local government Railway employees |

Open tracks Configuration of stations Targeting at risk populations |

Media and Communication Guidelines on Rail Suicide Promotion of Help Seeking to People in Personal Crisis Best Practice Techniques to Support Rail Personnel Surveillance and Monitoring on Open Track Areas Site Specific Initiatives on ‘Hot Spot’ Stations Training Rail Personnel – Suicide Risk Alerts Protocols with Health/Police – High Risk Individuals |

Activities and communication

In the context of the project, we organised and participated in conferences, workshops and knowledge sharing activities.

You can access the results of these activities by clicking on the following links.

|

Workshop on Railway Suicide Prevention and Impact Reduction for Railway Personnel, held as a satellite activity of the 2013 IRSC |

Session on railway suicide prevention at the IASP Conference, 2013 |

To come To come |

To come To come |

IASP, Oslo 2013

The CRISE organised a workshop session at the International Association of Suicide Prevention Conference on the topic of railway suicide prevention (PS3.4 - railway suicide: understanding and prevention).

Objectives of the workshop

Participants to the workshop

|

Brian Mishara, PhD, Director of CRISE, Professor, UQAM Cécile Bardon, MSc, Project coordinator |

|

Center for Resaerch and Intervention on Suicide and Euthanasia |

Risk factors for railway suicide and countermeasures to reduce the prevalence of railway suicide Abstract |

|

|

|||

The summary of all presentations as well as short interviews of several presenters will be availble here shortly.

Workshop on Railway Suicide Prevention and Reduction of Impact

Vancouver, October 11th, 2013, a satellite activity of the International Railway Safety Conference

Objectives of the workshop

- Learn about the incidence and characteristics of railway suicides and other fatalities in Canada and around the world

- Examine best practice models for railway suicide prevention and how they may be implemented

- Understand the impact of fatalities and critical incidents on railway workers

- Develop best practice models for prevention and intervention for workers involved in fatalities and other critical incidents

- Share knowledge and experiences on railway suicide prevention and help for workers

- Discuss consensus recommendations for standards and practices

Structure of the workshop

Formal presentations preceeded group discussions based on specific questions aimed at providing recommendations on suicide prevention and support practices.

Overall, there were 43 participants in this all day workshop, including representatives from the major Canadian railways, Transport Canada, the Railway Union, as well transportation police, Transport Canada and other regulators, and representatives from several railways and researchers in other countries.

Preventing railway suicides

The first session of the workshop addressed issues related to the prevention of railway suicides. It was introduced by a presentation by Brian Mishara, summarizing the content of the relevant sections of the website.

Reducing the negative consequences of critical incidents

The second session of the workshop addressed issues related to strategies to reduce the impacts of critical incidents on the railway network

Follow-ups and further steps

It is important to mobilise stakeholders on the issue of railway suicide prevention and reduction of negative consequences. A comprehensive cost effectiveness analysis is a powerful tool to reach this goal.

Pressure is another useful tool. However, it remains to be determined the type and amount of pressure to be exerted (and that there exists the means to exert) as well as the ones who should lead this pressure.

A grassroots approach can be considered, as it has proved effective with other public health issues.

A good strategy would probably be to invite the railway industry to join in a discussion and work group led by suicide prevention specialists, rather than expecting them to start something new by themselves.

Contact us

If you have any futher questions/inquires or would like any additional information, please feel free to contact us:

Brian L. Mishara, Ph. D., Professor, Department of Psychology, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), Director, Centre for Research and Intervention on Suicide, Ethical Issues and End-of-Life Practices (CRISE)

Cécile Bardon, Ph. D., Project Coordinator

Telephone: (514) 987-4832

E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Postal Address:

CRISE/UQAM

C.P. 8888, Succ. Centre-Ville

Montréal, Québec

H3C 3P8

Canada

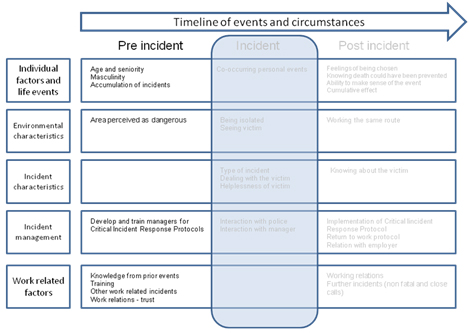

Post incident factors

These factors occur during the following days, weeks and months. They play an important role in the recovery process after the incident.

Incident related factors

These factors are linked to the critical incident itself and the period of time when the crew member is on site afterwards.

Pre-incidents factors

These factors occurred in the personal and work life of the employees before the critical incident took place. They influence the ability of the crew member to cope with the events to come.

Classification

The impacts of critical incidents on crew members are mitigated by a variety of factors. This section describes and analyses the effect of this factors. It is important to understand how they affect reactions to critical incidents in order to develop effective trauma prevention measures.

A specific element can act as a protective or risk factor depending on how it is experienced in the situation. The following description distinguishes the effects of protective and risk factors. These factors can also act directly and indirectly through the presence of others on the level of symptoms other employees have.